For the second year in a row, the Mets were able to draft one of the top amateur arms that had slid out of the first round for various reasons.

In 2019, top-20 talent Matthew Allan had teams convinced that no dollar amount would pry him away from a commitment to the University of Florida. The Mets rolled the dice and signed him with the 89th pick.

This past June, it was another talented right-hander: Missippi State sophomore J.T. Ginn would have been a top-20 pick — maybe top-10 had he played a full college season — before undergoing Tommy John surgery in March. Instead, the Mets grabbed at pick 52.

Ginn is no stranger to atypical draft developments. In 2018, he chose not to sign with the Los Angeles Dodgers after they selected him 30th overall. He was a draft-eligible sophomore this year (college players typically must wait until after their junior season) and forced the Mets to reexamine their strategy in an already unusual five-round draft.

What follows is a breakdown of what the Mets are adding to their system in Ginn, who joins Allan and 2019 second-round pick Josh Wolf to form an exciting trio of young arms in the lower minors.

Background/Statistics

Ginn was a two-way star for Brandon (MS) High School, serving as the starting shortstop and closer. He was a pretty damn good hitter, racking up a .415/.581/.829 line with 29 home runs in nearly 400 plate appearances.

On the mound though, Ginn was able to get by with a blazing fastball, to the point where he could enter a game, reach back for 97-99 mph, and blow three pitches past helpless high schoolers.

That may get you a good outing or two in college, but a pitcher needs a much more refined repertoire in the SEC, which is consistently regarded as the premier conference in college baseball.

The adjustments Ginn made allowed him to thrive in his freshman season.

He joined former — and now present — teammate Jake Mangum as the only Mississippi St. Bulldogs to win the SEC Freshman of the Year Award after tearing through the conference for 17 starts. Ginn struck out 105 batters to only 19 walks in 86.1 innings and allowed just one home run.

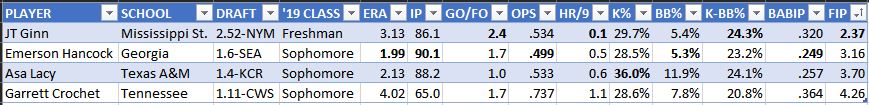

The primary reason for his success? Outside of that one home run, balls in play against Ginn were essentially glued to the ground. He coaxed 2.4 ground outs for every fly out, placing him second in the conference among pitchers with 100 batters faced.

I thought it would be interesting to compare Ginn’s numbers to the three SEC pitchers who were drafted in the first round last month. The results prove just how much the injury hurt his stock.

Perhaps as a side effect of throwing almost as many innings in one college season as he did in all of high school, Ginn dealt with minor arm soreness during the latter half of 2019. He did not play over the summer and lasted just three innings in his first start of 2020 before needing elbow surgery.

Fastball

Ginn’s max-effort fastball can ride up in the zone with high spin rates, but that isn’t what he sets out to do on the mound.

Instead, his primary offering is a two-seamer that utilizes a low spin rate to sink in on right-handed hitters.

For most of his first season, Ginn sat comfortably in the 93-95 mph range, with the ability to kick it up to 96-97 mph, though not for extended periods. The clips above, from his final start in the College World Series against Louisville, show him sitting at 89-92 mph, which could have been due to the arm fatigue.

Ginn’s raw spin is deliberately kept in the 1900-2000 rpm range. That in and of itself isn’t groundbreaking; pitches with less spin sink quicker than those with more spin (that’s why Gerrit Cole, for example, gets that rising effect on his fastball. His raw spin is one of the top marks in the majors).

But when he’s on, Ginn’s ability to keep the spin low at his velocity makes him stand out significantly.

Someone like Kyle Hendricks is known for his low-spin sinker, but he’s throwing it at 87 mph. Recent Mets acquisition Jared Hughes throws his sinker 75 percent of the time, but he isn’t blowing hitters away at 91 mph.

So when Ginn is hitting 95-96 mph consistently, that velocity/spin combo is going to be a real weapon. Though it isn’t his primary pitch, someone like the Reds’ Luis Castillo, with a 96.5 mph/2073 rpm sinker, provides a good model.

He does a solid job converting the spin into movement, usually posting spin efficiencies (spin that contributes to movement divided by total spin) in the 90-93 percent range. There’s certainly room for improvement there, especially if he’s going to be a 92-94 mph guy in the future.

Given his track record of throwing much harder, albeit in short stints, Ginn has the potential to find the velocity as a starter. If not, the movement profile on his fastball and the ground ball rates that it generates will serve him well.

Slider

Ginn’s potential top-of-the-scale offering is his slider.

Coming in at 83-85 mph, the pitch tunnels extremely well off the sinker. Both pitches look identical until the hitter has to make a decision, after which the sinker runs in on righties and the slider dives away.

While some sliders are wipeout pitches that emphasize horizontal break, Ginn’s slider emphasizes gyroscopic spin, which causes the pitch to drop vertically while moving very little to the side.

The goal for him is to get that spin efficiency figure as low as possible. At his 25-30 percent mark, the majority of his 2400-2600 rpms are caused by gyro spin, which does not affect movement (think of a football, the only thing making it drop is gravity).

But keeping some element of transverse spin gives the pitch its depth and life, and the result is almost a hard 12-6 curveball that comes in at 83-86 mph.

Hey look, it’s Castillo again. Here’s what a slider with a 22 percent spin efficiency looks like:

During May 2019, the #Reds Luis Castillo produced his best slider outcomes using a gravity slider; 78% gyro spin with a 1:45 spin direction. #BornToBaseball

Short-form movement: 0.3 hMov / -0.5 vMov pic.twitter.com/j5nroo2B7S— Michael Augustine (@AugustineMLB) May 20, 2020

Change Up/Fourth Pitch

Because Ginn’s fastball/slider combo worked so well during his freshman season, he rarely needed to turn to a third pitch. That won’t fly if he has dreams of being in a major league rotation in the future.

Ginn does throw a change up, but he struggled to find the circle grip consistently and sometimes went entire outings without using it. Reports from last fall said he had begun to show improvement with the pitch, but he was unable to show it off in front of scouts in the spring.

When he did throw it, the pitch was about an 85 mph offering with low spin. Depending on how he wants to build his repertoire, Ginn could aim for more gyro spin on the pitch (like his slider) or almost no gyro spin (like his fastball).

On top of that, Ginn might need a fourth pitch as well. During his freshman season he would fool around with a promising cutter during bullpen sessions, but it only made it into one or two outings. He surprised Rangers first-round pick Josh Jung with it during an early-season game against Texas Tech to strike him out.

It’s intriguing to think about a bullpen featuring Ginn at the back end, airing out high 90s sinkers with wipeout slider, but his acumen and feel for the game is too strong to not give him the opportunity to develop as a starter. He just needs an extra weapon or two.

Makeup

By all accounts, Ginn is an absolute pitching rat.

It’s fitting that the Mississippi St. Bulldog owns a bulldog mentality on the mound, which, combined with his work ethic in the bullpen and weight room, should make the Tommy John rehab process much easier.

He was a sponge for information and pitch data at school, frequently checking in with MSU’s analytics staff to figure out what he had been doing well, what he needed to improve on, and how he had been progressing and getting better over time.

The minor leagues are a grind. Ginn is suited for it.